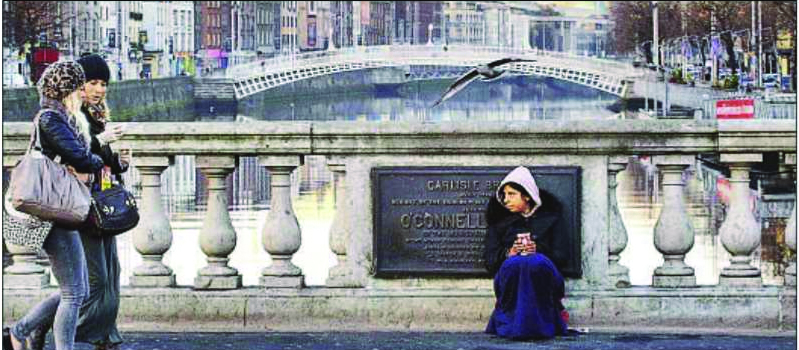

A woman begging on a street in Dublin. Ireland is currently facing the toughest budget measures in the nation’s history.

Five countries that faced meltdown in the past 20 years have all recovered – with or without IMF bailouts.

Thailand

It seems there is nothing that can stop the Thai economy: not violent protests on the streets of Bangkok, not cripplng floods, not regulatory concerns over the country’s largest industrial zone.

In 1997, the picture was very different. The Asian Financial Crisis started in Thailand, and its was the economy to fall furthest. The stock market dropped 75%.

The crisis was sparked by a collapse in the value of the Thai baht, and a disastrous currency float, which exposed an economy overstretched by real estate and foreign debt.

In August 1997, Thailand accepted a $17.2bn bailout from the IMF, subject to a number of conditions. A year after the crash, only 35 out of 91 finance and securities companies were left in Thailand. Some 1.8 million jobs were lost, and half a million foreign workers left the country.

But according to Dr Bhanupong Nidhiprabha, Associate Professor of Economics at Bangkok’s Thammasat University, Thailand had two distinct advantages to help it fight back: its own (then seriously depressed) currency, which boosted export demand, and a growing worldwide market. “The rest of the world were all expanding their economies, so we were able to export our way out of recession.”

Russia

A fall in global commodities prices – in particular, oil and gas – was a key reason Russia defaulted on its domestic debt in 1998. Russia, so dependent on hydrocarbons, metals and timber, went tumbling.

Foreign debt soared. The government fought to survive with a flurry of bond issues at ever increasing interest rates, finally provoking the crash in August. The results were dramatic. Almost all private banks imploded. The rouble was devalued by 75%. Millions of people lost their savings, wages went unpaid for months, and food shortage came back to haunt the population.

Yet the crash of 1998 also provided Russia a positive stimulus. “As it turned out,” said Anton Danilov-Danilian, who headed the economics department of the presidential administration at the time of the crash, “the economy only started to develop after the exchange rate was radically lowered, and our industry immediately got an advantage over importers.”

Brazil

In April 2009 Brazil’s uber-popular president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva announced that his country would lend some $10 bn to the International Monetary Fund, a further signal, he said, of Brazil’s growing importance on the world stage.

It was a dramatic turnaround for Brazil. In November 1998, the country had been forced to accept a $41.5 bn rescue package from the IMF, after economic crises in Asia and Russia made tatters of Brazil’s economy. Brazil’s ascent to booming Bric power is the story of a decade-long commitment to orthodox economic policy, a growing commodities boom and, more recently, massive government investment that helped pull the country through the latest global slump.

Moves to allow Brazil’s currency, the real, to float against the dollar in 1999, had been crucial to recovery.

Argentina

Over the last seven years, Argentina has enjoyed its longest economic bonanza since the end of the second world war. This is doubly startling because it followed an economic crash in 2001-2002 which called into question the economic survival of the nation.

By the end of 2001, Argentina had descended into a dark economic hole. The country had defaulted on its vast foreign debt, the national currency was devalued from one peso to the dollar to four practically overnight, and banks had closed their doors to the public, impounding the life savings of almost the entire middle class. Close to half the population fell below the poverty line as a series of five presidents replaced each other in rapid succession.

Argentina emerged from its economic wreckage by flaunting IMF guidelines.

Former President Nestor Kirchner, who won the 2003 elections, was able to pay off the country’s debt to the IMF in a bold move that allowed him to apply his own brand of growth, fuelled by spending, without abiding by IMF constraints at all.

Iceland

When the global financial system went into meltdown in October 2008, Iceland’s three biggest banks were 12 times bigger than the country’s economy.

In 2008, the banks started to run out of cash, and Glitnir was forced to turned to the Central Bank for a loan. It refused and instead took a 75% stake in Glitnir, prompting a domino-effect on the other banks.

Emergency laws were passed, the Icelandic krona plummeted, and by the end of 2008 national debt had hit 240% of GDP. Iceland was forced to go to the IMF, which provided a $2.1bn loan to be repaid in instalments. The IMF programme has now been revised three times, and is due to end in late 2011.

Iceland’s recovery is slow but gradual. Capital controls have been put in place to back up the currency, which has strengthened by 11.5% this year. After three years of economic decline, growth of 2% is forecast for next year.

The process, however, has not been painless. The IMF-programme has required massive budget cuts, that equalled 7.5% of GDP in 2009-2011. Tax-hikes have hit the pockets of Icelanders and public services.