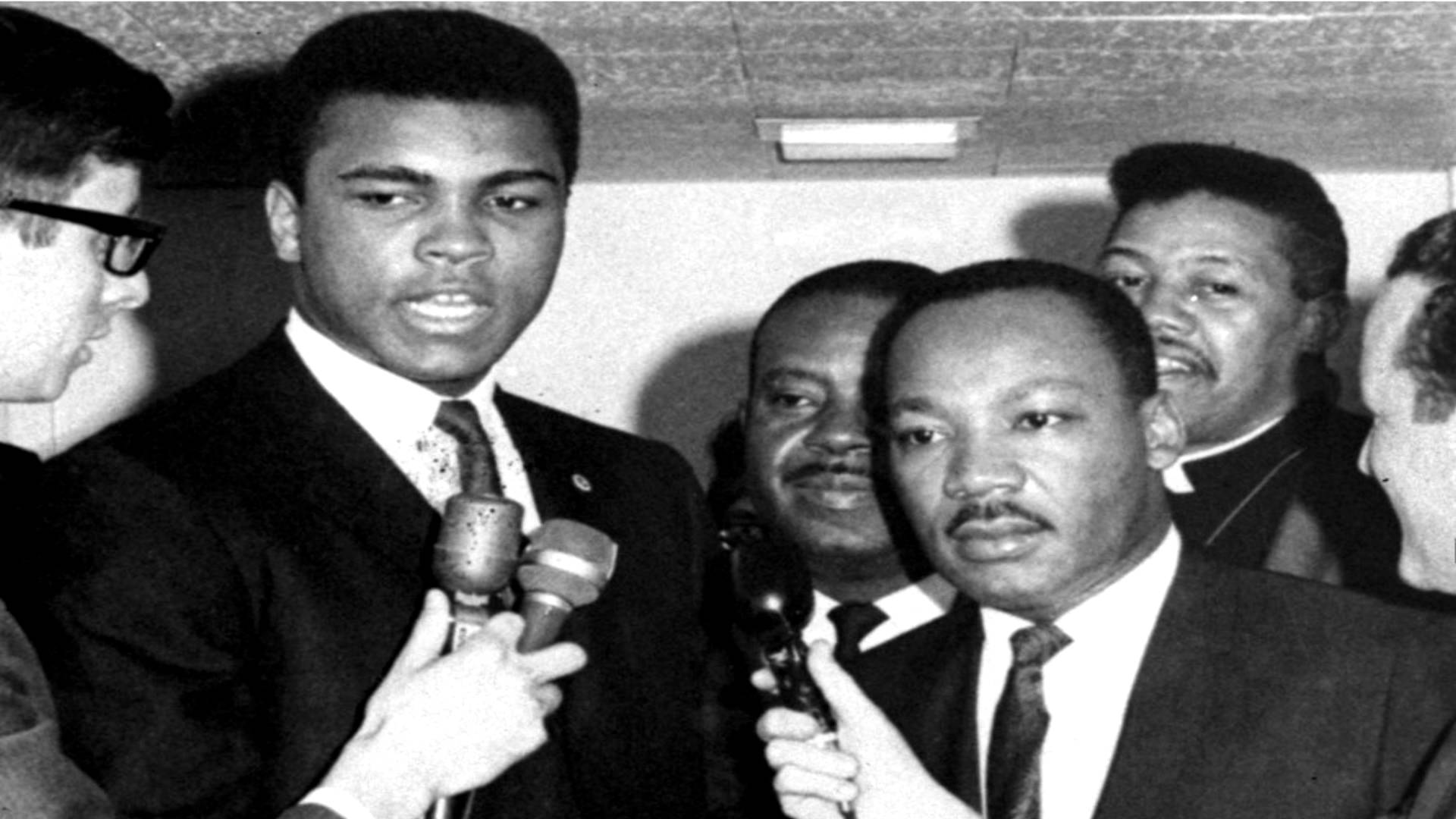

Well before Muhammad Ali passed away, the bulk of his legacy had already been buried. That he is being so generously eulogised after his death, even by Islamophobes and war mongers, is a good indication that the best part about Ali is no longer relevant. Sure, till the last Ali was a proud Black American. This passion, however, is not remarkable; many others have lived and died by this sentiment. But Ali was different. What set him apart was that he celebrated his colour alongside promoting peace and Islam; for him they were all the same. Nobody can ever doubt that Ali was an excellent boxer, probably the best heavy-weight ever, but, in his glory days, he was a great deal more than just that. When he converted to Islam, soon after he became the world champion in 1964, it was an affront of the highest order to the White establishment. He made it much worse by refusing to fight in Vietnam because, as he said, his religion forbade killing innocent people. Are you listening, Isis and Taliban? In line with his understanding of Islam, Ali wanted to be recognised as a conscientious objector. But he did not stop there. He went on to ask why he should enlist and put on a uniform just to “go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people…who are fighting for their own justice”. So now not only was Ali a Muslim, he was also forgiving Communists. The establishment was furious, but the Supreme Court upheld his plea. America has come a long way since then, but Ali has hardly intervened in the many other wars that the US has waged against other “Brown people”, who are “10,000 miles from home”. Surprisingly, he has had little to say about the growing Islamophobia in his own country in recent times. In a sense, Ali has been complicit in burying the liveliest part of his legacy. He left the wrap, but chucked the gift. The most telling illustration of Ali backing down from what he once upheld was his acceptance of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Horror of horrors, he received this award from George Bush Jr, a man who encouraged the first great, post-Vietnam American offensive overseas. Not just that, Bush Jr, also officially inaugurated current-day American Islamophobia when he likened his intervention in Iraq to another “crusade”. Yet, none of this stopped Ali that day from shaking hands and smiling with George Bush Jr. Ali was never known to wince, not even with the hardest punch. It would have, however, been comforting to many had he squirmed just a little when Bush called him a “man of peace”. It is hard to imagine Muhammad Ali accepting such an award from a man such as Bush when he was truly the “greatest”. He was at his peak as a boxer from 1964 through to the seventies, but during all those years he was also at his peak as a preacher of peace and Islam.

The latter-day Ali did not show this full-bodied greatness. This is why it is so easy for all kinds of political reprobates to own him today. Why even Donald Trump had the gall to issue a statement saying Ali was: “A truly great champion and a wonderful guy”. That he could pronounce this and not fear a backlash from his redneck, gun-toting, bible-spouting gang tells us a lot about how Ali’s legend has been sanitised and is now establishment-friendly. Not surprising then, Ali’s condemnation of Islamophobes in 2015 carefully avoided mentioning Trump by name. Even so, it is still hard to be harsh on Ali; his one-time ring opponents feel the same way too. When he lost, the victor felt rotten and if he won, the vanquished still felt good. When Larry Holmes turned Ali into a stand-up punching bag and slugged him relentlessly, he did not go home a happy man. After the bout he said: “All I achieved was money.” That was to be the aging Ali’s last fight, long overdue. Then there was the famous Kinshasa encounter against the formidable George Foreman. Stringing him along for seven rounds with his, now famous, rope-a-dope tactic, he suddenly unleashed a series of sharp left-right combinations. Unbelievably, Foreman’s knees buckled and he fell slowly like a giddy ballet dancer. His humiliation was great, for no matter from which angle you took in Foreman, the man was a monster. He was humiliated terribly in defeat, but he too, on hearing of Ali’s death, said: “I lost my best friend.” It did not matter who Ali boxed. From the time he met Floyd Patterson, right up to the fight when he took the title away from Leon Spinks, the audience was divided along predictable lines. His opponent could be darker or lighter than Ali, but for the bulk of white people by the ringside, or watching fight night on television, that did not matter. Symbolically, Ali’s opponent was their white man for the night and they cheered him on hoping that Ali would fall. When Ernie Terrell, the white man’s black boy, taunted Ali and called him Cassius Clay, he was destined for slow torture. Ali toyed with him for 15 rounds and every time he punched him, he asked Terrell: “What’s my name?” His feats in the ring have passed on to boxing lore and will live endlessly on YouTube. Sadly, his other accomplishments, which together made him the “greatest”, are now fading fast. They are on a few memory tapes but these are hardly as durable as YouTube is.