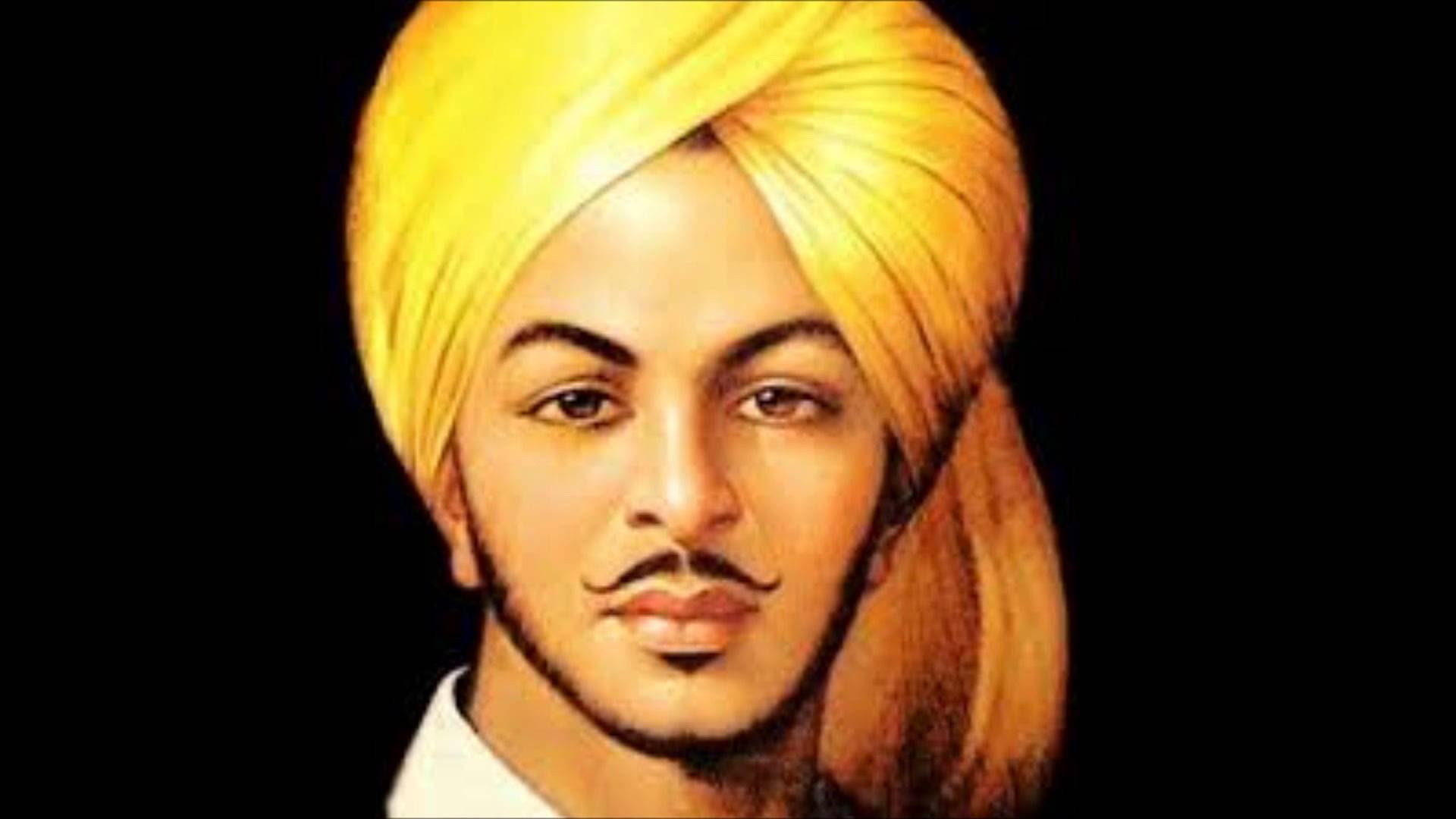

Bhagat Singh was one of the most original Marxist thinkers in the country who not only dreamt of freedom from the British Raj but also of an egalitarian and secular India.

Two days before his 85th death anniversary, Bhagat Singh – the Marxist revolutionary hanged by the British at 23 – trended on Twitter, as people lashed out against Congress leader Shashi Tharoor for comparing Singh with the latest Left-liberal sensation, JNU student leader Kanhaiya Kumar.

Singh’s political acumen, revolutionary activity, popular appeal and controversial execution made him a national figure at a much younger age than Kumar.

Kumar was, till recently, a campus politician who shot to prominence and won hearts because of the state’s knee-jerk reaction to arrest him, misleading media trials and his furious critique of the overall policies of the BJP-led central government. Nonetheless, the basis for the comparison – both young men are “Marxists … passionately committed to their motherland” – is broadly correct. Just like Kumar spoke about ‘azaadi’ from people who are “looting the country”, Singh too had said in one of his last messages on March 3, 1931, that the struggle in India would continue as long as “a handful of exploiters go on exploiting the labour of the common people for their own ends. It matters little whether these exploiters are purely British capitalists, or British and Indians in alliance, or even purely Indians”. But there are prominent differences. Singh never joined the Communist Party of India (CPI), established in 1925-26, of whose student body Kumar is a member. Yet, the Indian Left has always appropriated Singh as an iconic hero who, according to former CPI (M) chief Harkishan Singh Surjeet, gave a country a course “opposed to the one pursued by Congress”. But today the Left in India has many hues, and it’s difficult to predict how Singh – a believer in anarchism – would have chosen to fight for the “liberation” of his countrymen in today’s India. If Singh had been alive today, would he have joined the parliamentary Indian Left parties? A study of Singh’s politics indicates the answer is more complicated. For example, Delhi University professor Apoorvanand wrote in an article last year that “…Bhagat Singh was not impressed by the nationalist rhetoric of (Netaji Subhas Chandra ) Bose and finds Nehru intellectually more challenging and satisfying”. He wrote that Singh had written in 1928 that “Panjabi youth should go with him [Nehru] to understand the real meaning of revolution…” and this article by the revolutionary has been ignored by the Left, perhaps because it doesn’t fit into their narrative. Therefore, it’s correct to say that cherry-picking and appropriation by Indian political parties do not do justice to Singh’s political ideology. Shahnawaz Hussain , spokesperson of the BJP, tweeted the comparison was an insult, adding that Singh had “kissed” the noose saying “Bharat Mata ki Jai”. Really? Hussain perhaps got carried away because there seems to be no historical record suggesting that Singh’s last words were “Bharat Mata ki Jai”. Media reports — for example the lead story on The Tribune on March 25, 1931 — say that the cries that emerged from the jail just before the hanging of Singh and his comrades Sukhdev and Rajguru on March 23, 1931 were of “Inquilab Zindabad (Long live the revolution)” — a Leftist war cry popularised by Singh. Historical records — for instance writings by Bhagat Singh scholar Professor Chaman Lal — say Singh was reading Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin’s biography until minutes before his execution. “Making mockery of history. Bhagat Singh raised Bharat Mata ki Jai slogan while he was on the gallows. Putting your own words in his mouth,” tweeted historian S Irfan Habib and author of To Make the Deaf Hear: Ideology and Programme of Bhagat Singh and His Comrades. Habib added, “All historical records show that Bhagat Singh raised just 2 slogans Inquilab Zindabad and Down with Imperialism. And it’s no surprise.” But Hussain is not the only one to appropriate Singh with one casual stroke. Time and again, the Hindu Right has tried to do the same – by portraying Singh as a gun-toting militant nationalist. Sketches of him – sporting a hat and with twirled moustache – is a common feature on many political posters. Such propaganda can be easily dismissed by anyone who goes through Singh’s writings, messages and speeches. Here was a firebrand Leftist and an atheist who vociferously criticised the agendas of communal politics and capitalist economy. Moreover, Singh had, later in life, questioned the role of armed struggle in the revolutionary movement. In a piece, while his trial was ongoing, Singh wrote in December 1929, “Revolution did not necessarily involve sanguinary strife. It was not a cult of bomb and pistol. They may sometimes be mere means for its achievement. No doubt they play a prominent part in some movements, but they do not –for that very reason –become one and the same thing. A rebellion is not a revolution. It may ultimately lead to that end.” Singh was one of the most original Marxist thinkers in the country who not only dreamt of freedom from the British Raj but also of an egalitarian and secular India. In fact, such political farsightedness set him apart from his contemporary revolutionaries. Bhagat Singh and his comrades, like the renowned historian Bipan Chandra wrote in India’s Struggle for Independence, “…made a major advance in broadening the scope and definition of revolution. Revolution was no longer associated with mere militancy or violence…it must go beyond and work for a new socialist order, it must ‘end exploitation of man by man’.” Every time today’s politicians drag Singh and appropriate him for their political slugfest, the true legacy of one of India’s bravest martyrs is insulted.